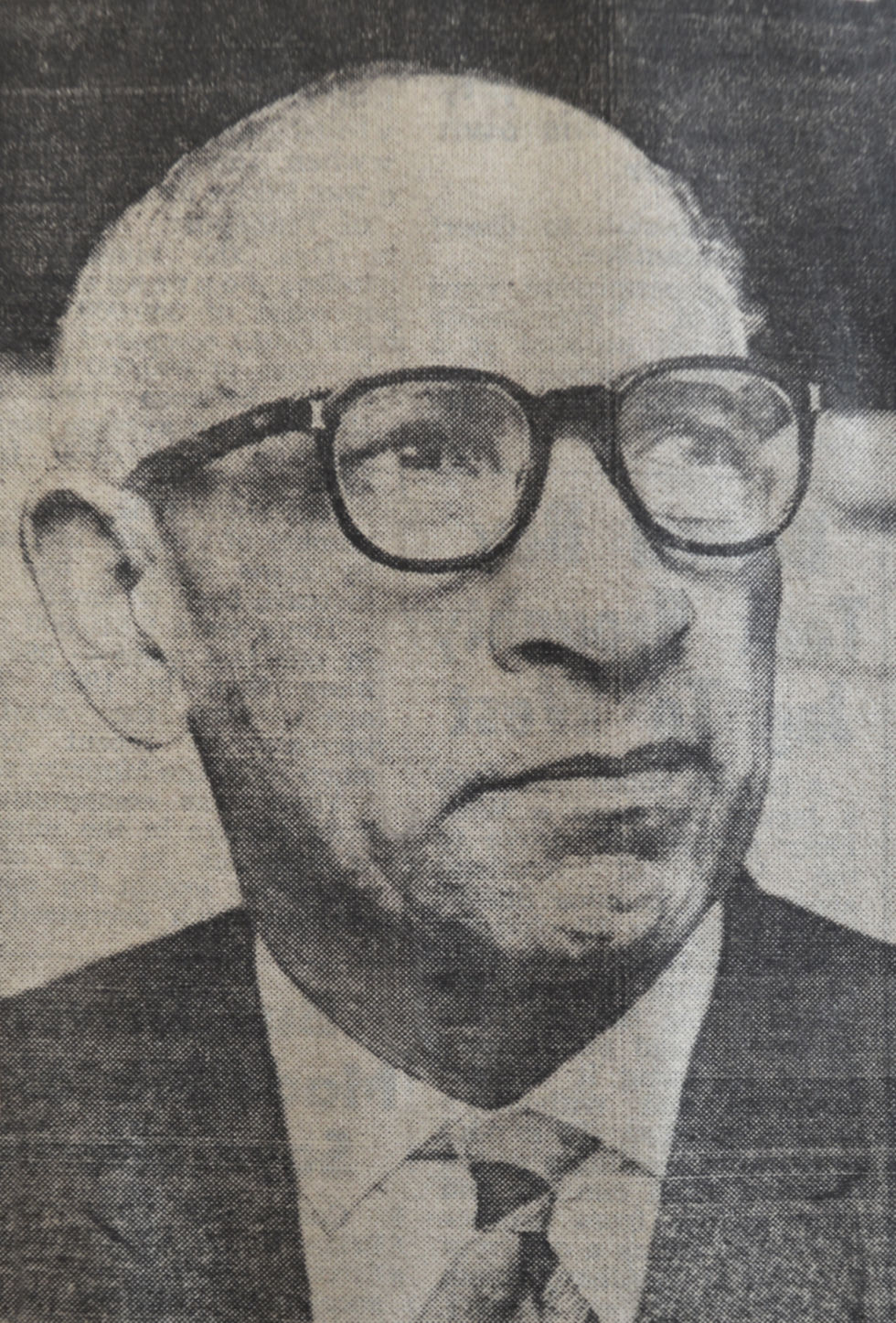

The Story of Kalidas Datta Choudhury, student of Dundee Technical College 1952-54

- woventogetherdundee

- Sep 29, 2024

- 6 min read

In the 1950s, India was waking up to post-independence realities. My father, Kalidas Datta Choudhury (known as ‘KD’) was also wondering about his future. He had completed a degree in Commerce, but a future of double-entry bookkeeping just did not appeal. As the younger son of a landowning ‘Zamindari’ family in Sylhet, the laws of primogeniture weren’t in his favour and he needed a profession. When his elder brother mentioned the newest up and coming industry – jute – his interest was piqued. Following Partition, the once mighty Calcutta jute industry was traumatised – its mills were separated from the source of raw material which now fell in East Pakistani territory. The Indian and Pakistani governments were giving a lot of attention to its survival. More importantly, the Scottish ‘jutewallahs’ that had run the mills were leaving and career paths for Indians were opening up more swiftly than in other industries. Jute had huge commercial potential and excellent perks, including free living quarters.

So, the next step was to apply to Dundee. The fates were favourable as Dundee Technical College, struggling for local students for its Jute courses, was welcoming international students. The Scots had benefitted from their training at the Technical College, which had given them a definite advantage in mill management. Mill managers and foremen from Dundee were in demand in Calcutta and few mills on the Hooghly were without a Dundee overseer, manager or mechanic. With my father’s generation, the time had come for Indians to acquire this training and take advantage of the career opportunities this would bring them. He set sail from Bombay in 1952 on the SS Chitral, carrying with it hundreds of Indian students from Calcutta. They hailed mostly from middle-class, professional families, some of whom had used family savings to fund the trip.

My father arrived in Dundee with a pocket full of money - almost £50. The College had provided a list of approved digs via the British Council in Calcutta and he chose one of the more expensive ones, in Springfield, off the Perth Road, costing a pound (20 shillings) a week. The only house to boast an inside loo, it was in a cul-de-sac of gracious Georgian houses. His landlady, Mrs Rydale, was a war widow and like many others had had to be creative in supplementing the army pension. Taking in lodgers earned a decent living; all one had to do was register interest with the College, who had a list of basic criteria. Once on the College’s official list, details were shared via the British Council across the world’s students.

House rules were strict. Shoes had to be vigorously wiped on the doormat – not a whisper of dust or a drop of rain could make it past the front porch. Umbrellas must be left in the stand in the hall to the left of the front door, and coats hung in the coat cupboard. A wooden Harris coat brush was placed handily on the cupboard shelf to provide a final dusting down before leaving the house. Breakfast was at 8am and dinner at 6pm, with supper at 9pm. So unbending were these rules that they were to become like second nature to my father and much, much later to us as a family.

To get to college was only a short tram ride from Perth Road to Bell Street. On the first day, new students were directed to nearby Caird Hall for a personal welcome from the Principal, Mr John R Whittaker. The first-day portrait (seen above) of the students in their suits and tightly knotted ties betrays a nervous energy of anticipation. My father remembered requesting his landlady to press his suit for the occasion. Her crisp response – “You don’t want your suit to be shiny like a policeman’s – just hang it up in the bathroom, dear” – was met with scepticism, used to as he was to the rigours of dhobi starch. The suit, duly steamed at bath-time, was indeed immaculate the following morning. The freshers’ welcome included lavish plates of Jammy Dodgers washed down with Robinson’s orange barley water, mindful of cultural sensitivities. The Principal, Mr Whittaker, addressed them from a podium, welcoming them to Dundee and the College facilities that would enable them to build great careers in jute. Father had officially started the first stage of becoming an Indian jutewallah.

The first thing one must do to have any kind of social life in 1950s Dundee was to dance. For the young Indian students, this was a difficult passport indeed. There were private lessons given by an enterprising mother and daughter duo for the princely sum of £5 a session. Not many could afford that, but a few like my father were happy to invest in this clearly important skill. Lessons were held in the anonymity of the basement, below the dance hall on Thursday evenings. My father made his way there after tea and a furtive group of a few other students. Here, week on endless week, they mastered complex footwork for the Waltz, Foxtrot, Quick Step, Rumba and Chachacha with either of the instructors, with a “Don’t look at your feet, look at your partner” testily shrieked out every few minutes.

Father, showing promise, diligence and enthusiasm, was promoted after what seemed an eternity and enormous fortune, to the upstairs ballroom on Thursday evenings for free practice sessions. Tango manoeuvres remained a mystery to the end. His equally keen Calcutta classmates preferred Students’ Union dances (a shilling and sixpence) learning with and getting to know willing partners at more democratic prices. Ladies’ Choice was when there was nowhere to hide: the famous ‘Palais Glide’ as the women took the lead with confident speed still brought a validatory smile to his face some 70 years later

My father’s favourites were the Palais De Danse with its sprung floor on South Tay Street and Kidd’s Rooms in South Lindsay Street. There were others: Robbies, the Chalet on Broughty Ferry Esplanade, the Hollywood Hall in Lochee and the Locarno on Lochee Road. Weekend afternoons were mostly spent queuing on South Tay Street for tea dances at the Palais as early as 2pm for the 3pm start time. These sessions finished by 5.30. The night still being young, one could move on to Kidd’s Rooms, or take the train to Aberdeen. Black Fridays were special occasions, for which Father invested in a set of tails and bow tie – others, more practically, hired theirs for the night.

Otherwise, dress was still formal – suits for men a must and Father paired this with his spectator brogues, cutting a dashing figure, in his opinion. The elegant students from the sub-continent provided an exotic allure to the girls and these young men, heady with unaccustomed attention and far from family restrictions, were in turn open to temptations, even forbidden ones – at least one of my father’s close friends conveniently ‘forgot’ he had left a wife behind in India.

Father joined the Burns Society and the SNP – many Indians fresh from their own independence had sympathy for the Scots. Hogmanay for Technical College students was celebrated at Caird Hall. My father remembered his first event with great clarity. The 1953 party was fancy dress – guests were to dress as a representative of another country. To stand out from his friends, who dressed as Indians, Father dressed as a Burmese, in a lunghi (sarong) and vest. Within minutes of his arrival at the Hall, he couldn’t feel his lower body. At two degrees centigrade, the Dundee winter didn’t favour any attempts to invoke a tropical vibe and the next thing my father knew he was being rushed to a small room by the fire to be revived.

On his return to Calcutta, he joined Anglo India Jute Mills and it felt as if he was back in Dundee. Surrounded by Scots, amid immaculate grass lawns and tennis courts, living in staff quarters that had mantelpieces and verandahs, he played billiards and tennis and celebrated Burns Nights. My father’s abiding love for Dundee rubbed off on us and we grew up eating porridge and marmalade for breakfast, Macher Jhol (fish curry) for lunch and Dundee cake at Christmas. We thought it all pretty normal, really.

Written by Anushua Biswas

Comments