The Life of Dr Dhani Ram Saggar Part One – A “Wee Indian Doctor” in Dundee

- woventogetherdundee

- Mar 5, 2025

- 8 min read

In 1926 a young man called Dhani Ram Saggar left his family home in Deharru, a village in Punjab, northern India, to travel by land and sea to the city of Dundee. The 34-day journey took him south by train and boat to Sri Lanka where he boarded a ship bound for Gravesend, calling into such places as Aden and Marseilles. After disembarking and finding his way to London for a train to Dundee, he arrived at Tay Bridge Station in pursuit of a medical education at Dundee’s Medical School.

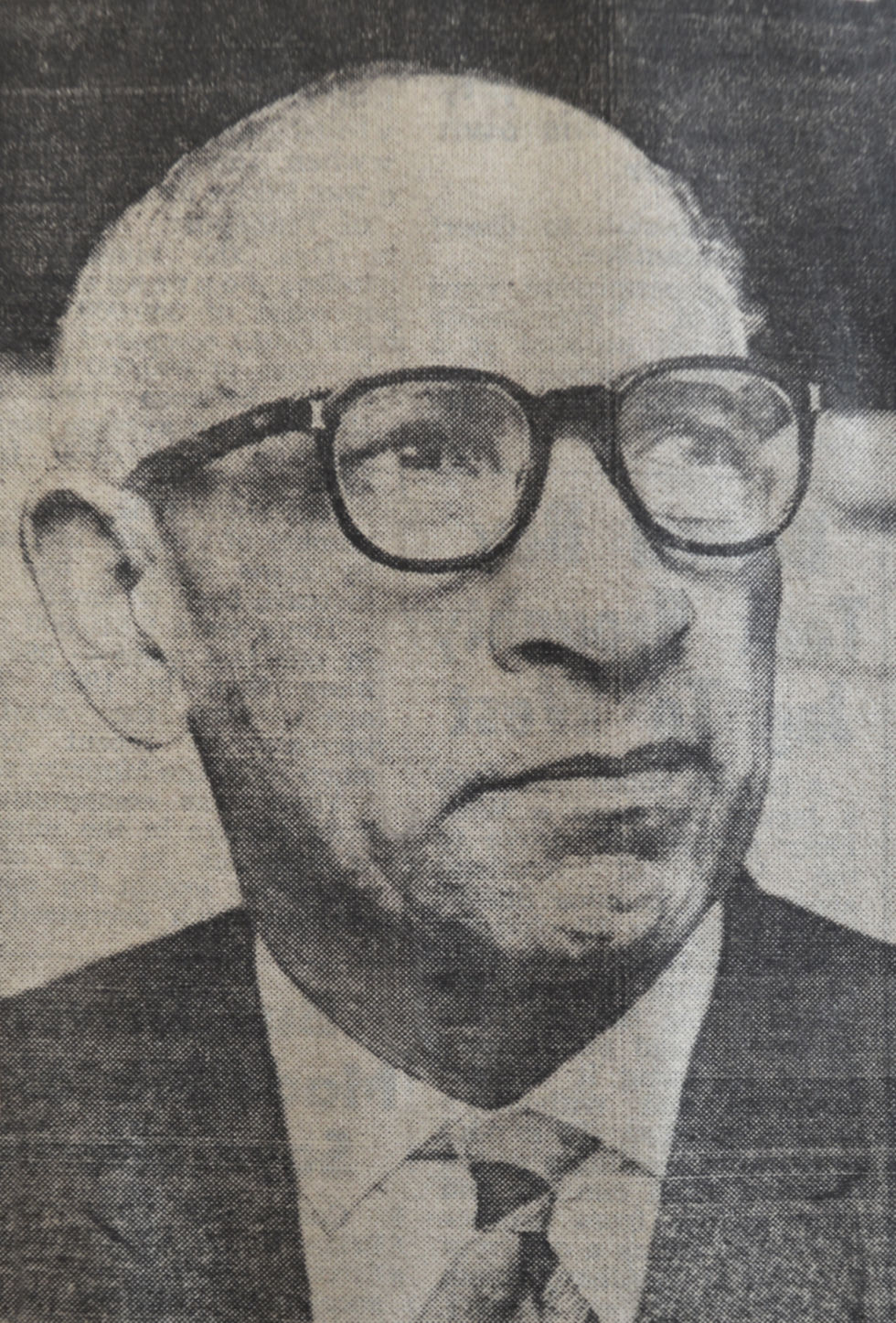

Dhani joined his brother Jainti at his home at 8 Byron Street. Much has been written about Jainti Dass Saggar, medical doctor, local councillor and public speaker, but far less has been written about his younger brother. Jainti’s daughter Kamala Stewart described her Uncle Dhani as: “Medical Practitioner. Family Historian. Avid Traveller. Writer. Philosopher”. This two-part blog will discuss Dhani’s life as a doctor in Dundee and his role as a humanitarian.

Dhani grew up with five siblings in “relative posterity” in a large house with wooden shutters with bars on the windows, high ceilings with “ornamental arches on doors” on narrow cobbled streets surrounded by fields. His father, Ram Saran Dass, worked as a merchant and brought up all his children with the aim that they “would be well educated and would be followers of Gandhi’s principles of non-violence”. In one of Dhani’s public talks, ‘The Essence of Religion’, he describes his mother, Sarhi Devi Uppal, as “unlettered, industrious and helped everybody in need in the village.”

Along with Jainti, Dhani attended the local village school where the children wrote with a stick on a wooden board coated with dried mud. He then went to complete his secondary education in a “grand looking building” in Khanna, a five mile walk away from the village. Encouraged by his father, Dhani followed in his brother’s footsteps, going to study medicine at the University of the Punjab before coming to Dundee.

At home there was considerable unrest under the British Raj. During the Great War, several mutinies planned by Indian Nationalists and by the British Indian Army had been thwarted with harsh repercussions. Then in 1919 at a peaceful demonstration at Amritsar, close to the Saggars’ home, over 2000 people were injured and killed. This undercurrent of colonial violence was probably another factor for Dhani to leave.

Two other Indian students, Nawab Ahmad Kuriashy and Sukev Pershad Bhatia, matriculated with Dhani at the same time at Dundee’s Medical School, then part of the University of St Andrews. Unlike Kuriashy and Bhatia, who failed the English entry exam, he seemed to have a decent understanding of English which put him in good shape for his studies. He entered as a second-year student having secured his place by passing the First Professional Examination in Science back home, and he did so well that in his first year in Dundee he won a First Class Certificate of Merit for Junior Anatomy.

One of many courses Dhani had to study for his degree was Midwifery. In an interview given to the Dundee Courier in 1967, he recounts a few memories from his student days:

“As students we always ran to maternity cases. We had to attend a given number of births in the patients’ homes during our maternity training. Our professor at Dundee Royal Infirmary always insisted that the student was there before the baby was born and did everything necessary in the case – right through to bathing the new arrival, putting on its first nappy and dressing it. If we arrived late and could not honestly say we had seen things through from start to finish the case did not count. So we ran to the home of the expectant mother to try to beat the stork.”

Dhani passed most of his exams without having to re-sit. Unfortunately he failed the final year exam in Surgery but six months later he passed, graduating with MB ChB (Bachelors in Medicine and Surgery) in January 1931.

After graduation, Dhani began practising medicine and set up a surgery at 51 Cobden Street in Lochee where he first set out to help and treat the people of Dundee. He would go on to serve as a General Practitioner for 35 years. During that period the city’s economic fortunes changed considerably. 1931 was the height of the Depression, with unemployment in Dundee reaching an all-time high. He retired in 1966, a time of relative prosperity for the city, with new industries and massive new housing developments underway. In a series of interviews in the Dundee Courier in 1967, he recounts his memories of the patients he helped, how the health profession changed with the advent of the NHS and how the people of Dundee welcomed “the wee Indian Doctor” as he was known.

In the first few years, he set out on foot from his surgery with his doctor’s bag, scaling the many stairs of tall tenements, navigating through the dark passages of closes, in “fair weather and in deep snow, seven days and nights a week”, often to “weary old homes in a smoke enshrouded hollow.” In the early days he would often get lost in “dimly lit” closes and crowded tenement blocks. He eventually found that the solution was a “walk through the close to the back courts, peering upwards to see the window that was lit in the middle of the night,” then shouting “to ask where the doctor was wanted before I started to climb”.

Three other Indians are known to have set up as GPs in Dundee before Dhani - Dr Ram Parshad Sood, Dr Ajudhia Nath Nanda (both of whom remained only a few years) and Dhani’s brother Jainti. Little is recorded about how the local population adapted to being tended by a doctor from India but Dhani does say: “When my brother and I were in our early days as practitioners most of the Indians in the city were pedlars. That was why we sometimes knocked on a door and a harassed householder said ‘nothing today thank you.’ We had to explain ‘I'm the doctor.’” More positively, he also noted: “They did not think of me as a foreigner or different in any way… people were kind to me and made me one of their own.” He also reminisced about how he found it difficult to understand the local dialect: “I had to learn many things from my patients. Imagine the slight perplexity of the young doctor from the Punjab when a Lochee worthy walked into the surgery to announce, ‘eh hiv a bealin’ in meh oxter.’ [boil in his armpit]”

Dhani had evidently been accepted as “one of their own” by November 1934, when the Courier reported that he was included along with Dundee Rep Theatre and the Telephone Exchange in a series of prank phone calls from “six girls who caused a great deal of trouble by sending false messages.” While the theatre thought they had lots of seats booked and the Telephone Exchange forwarded calls to hospitals, Dhani was asked “to attend certain patients, and when he called at the addresses given he found that the calls were bogus. This had involved a waste of time and a waste petrol.” In court the girls pleaded guilty.

Dhani’s practice gradually expanded, from “Whorterbank, Burnside Street, Kirk Street, South Road, Liff Road, Marybank Lane” across to the Hilltown. After a few years he was able to buy a car, allowing him to visit patients in areas such as Douglas, Broughty Ferry and Invergowrie. His first car cost £10 and often needed a push to “get it started before jumping in”. Unlike Jainti, who was prone to incur repeated fines through bad driving, Dhani is only reported as having one offence – in November 1939 the Evening Telegraph reported that he was fined 5 shillings for not having his lights on.

The advent of the NHS in 1948 brought many health benefits to people’s lives. Dhani remarked: “In these much easier and more enlightened days of the Health Service, all medicines and dressings are free along with the doctor’s visit”. However, he noticed that people became less self-reliant: “In my early years the patients had to make many of their own dressings. If someone had lumbago he made a poultice and put mustard on it. That was a cure. Today there are lots of people who cannot make a poultice. Rubbing with liniment was once commonplace. Now it is not used to the same extent. Before the war many people were experts in massage.”

However, Dhani was well aware of the hardships of Depression-era Dundee, when those living in poverty could ill-afford food and sometimes could not pay their medical bills. He recalled: “This was at a time when many people’s health troubles stemmed from malnutrition. They ate bread and margarine with occasionally a little jam.” In the 1930s, doctors’ charges were “3s 6d for a visit and 3s for a consultation” and the patient then had to pay the chemist if medicine was needed. For an ambulance that would be another 2s 6d. Dhani remembers some patients would get out of paying their bills. One patient he mentions, an elderly lady who lived in the Tipperary area of Lochee, insisted on him driving her home after her visit to his surgery and then telling him “Of course, I canna pay you for this visit.” He continued: “People had to be careful lest their bills mounted. Often if I said I would call again to see a patient this was countered with a cautious ‘we'll see hoo he gets on and if we need ye we'll send for ye.’”

Dhani adopted a Gandhian philosophy to health and care, helping his fellow human without personal rewards. By the time he retired, there were around 20,000 Indian and Pakistani doctors coming to work for the NHS. They brought a similar philosophy, filling in gaps in “deprived” and “unpopular areas or ‘hard to fill’ specialities” and it is now recognised that the NHS may well have collapsed altogether without this influx of junior doctors from overseas.

Throughout Dhani's life until his death in 1973, he never strayed too far from his Indian roots. He sought to raise awareness creating links between Dundee and India and this influenced the next part of his life as an advocate for peace, secretary of the Dundee branch of The Friends of India Association and service to charity. Find out more in Part Two.

By Johanna Steele

Sources

Dundee Courier, 31 January, 1 & 2 February, 1967

“Jainti Dass Saggar; From Deharru to Dundee” publication based on a lunchtime lecture to the Friends of Dundee City Archives by Kamala Stewart, 2014, available online at https://www.bookemon.com/flipread/435118#book/

“The Essence of Religion: An Address delivered by Dr Dhani Ram Saggar at service in Williamson Memorial Unitarian Church, Dundee, 19 January 1964” (Local History Centre, Dundee Central Library)

“Jallianwala Bagh massacre” - en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jallianwala_Bagh_massacre

Dundee Courier 24 November 1934

Dundee Evening Telegraph 3 November 1939

“How the UK's NHS was built on the backs of Indian doctors and nurses” 24 October 2024, at https://www.firstpost.com/explainers/uk-nhs-indian-doctors-nurses-13828727.html

“Making Britain - Discover how South Asians shaped the Nation 1870 to 1950,” Open University, 2010, at https://www5.open.ac.uk/research-projects/making-britain/content/friends-india-society

B Bhala, A Bhala & N Bhala, ‘A Historical Look at Indian Healthcare Professionals in the NHS’, Sushruta Journal of Health Policy & Opinion, vol 12 no 1 (2000), pp19-21.

Comments