Kalam Chowdhury: A Community Pioneer

- woventogetherdundee

- Jan 18, 2022

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 7, 2023

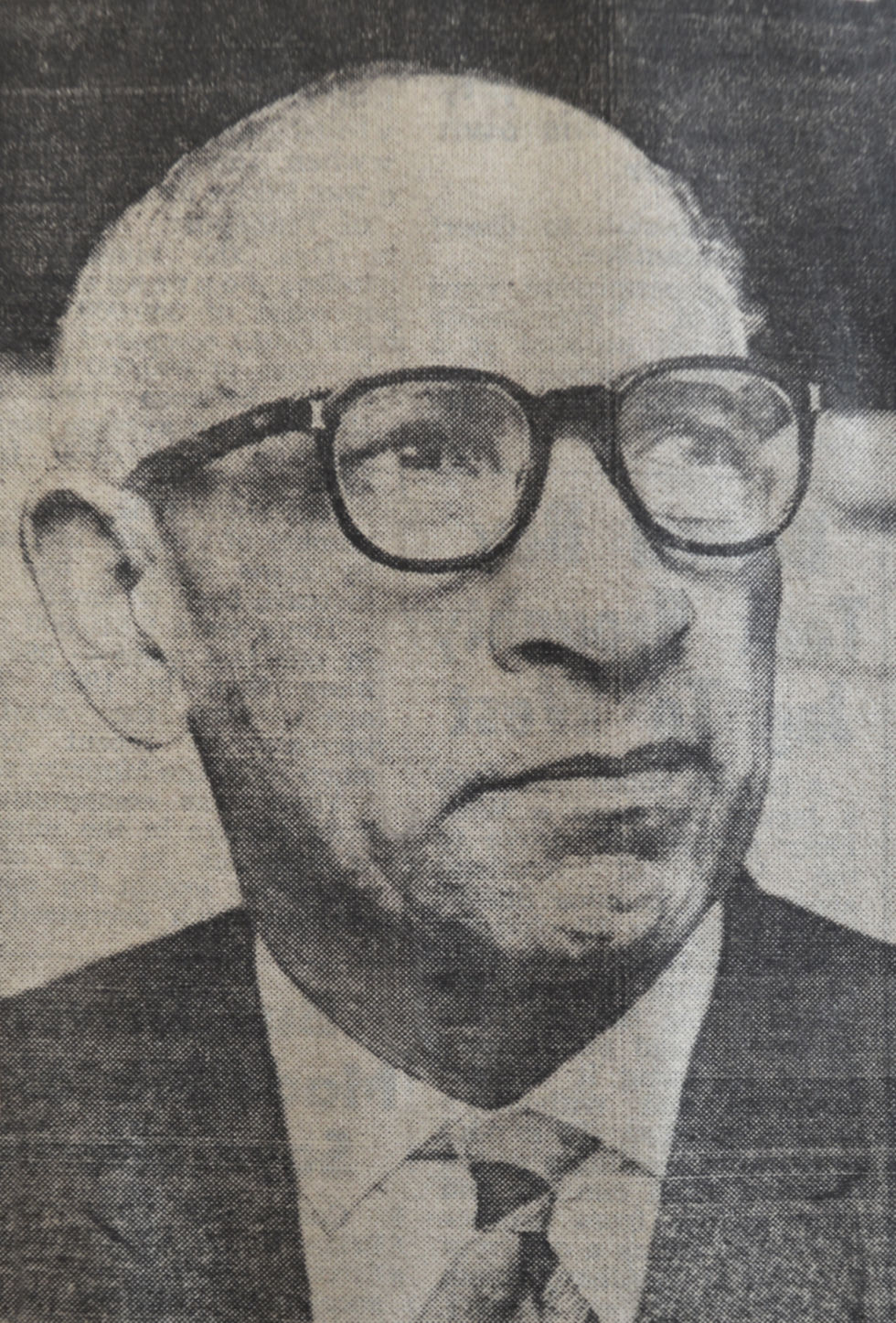

The story of many members of the Dundee Bangladeshi community is intertwined with jute. Historically Dundee sourced much of its raw fibres from Bangladesh, and in turn, many people from that country went to Dundee either to work or be trained here. Abul Kalam Chowdhury is one of the early pioneers of that remarkable community that made such a significant contribution to the history of the city.

He grew up in a rural farming community in East Pakistan, before graduating with a science degree from the University of Dacca. Employment opportunities were limited in his area though, with jute production being the main industry there.

To give himself good employment prospects in East Pakistan he realised he had to get training in jute production that would allow him to become a manager and develop a good career, and so he managed to get the funding together to come to a well-established 3 year Jute Manufacture Diploma course, starting in September 1967 at what was then the Dundee College of Technology.

Things did not turn out quite the way he expected. His qualification took him a year longer than expected, and when he qualified in 1971 the Bangladesh Liberation War in East Pakistan had begun. It wasn’t possible for him to return to his homeland at that time.

For reasons that aren’t clear, he chose to support himself with work in the catering industry. Perhaps he saw how the jute industry was in decline in Dundee and didn’t see good career prospects there, compared with what he already knew of working in catering during his student days.

Whatever the reason, it was an important decision, because it shaped his future, leading to him staying in the UK for the rest of his life, and becoming one of the earliest members of the Bangladeshi community in Dundee.

The next few years saw him working in restaurants in London, and then back in Dundee, sharing the culture of his country through the food that he made. Eventually, he managed his own business – the Anglo-Indian restaurant in Dundee, which then led to him owning and managing two more in the city. His friend Abu Karim mentioned that his training in Jute Management would have prepared him well for this, as he managed 8 staff in his first restaurant alone.

A tragic and momentous event in Kalam Chowdhury’s life however, indirectly led to him establishing an organisation that brought the Bangladeshi community in Dundee closer together. In 1980, his wife died in childbirth. It was his wish, and the wish of her family in Bangladesh, that she should be buried there. He managed to arrange the transport of her body, but he found that there was no clear process arranged for doing this, and it was also very expensive.

At the end of this heart-breaking time for him, he realised that this was something that would probably happen again to others in the community, and he decided that there should be support for grieving families to help them make and pay for the arrangements to send their loved ones back to Bangladesh. This led to the formation of the Bangladesh Association in Dundee, an organisation that is still in existence today. Its work helping families and the community has grown to include all sorts of other projects, such as arranging events, and fundraising for other causes, including emergency relief for disasters in Bangladesh, and for building the new Mosque on Miln Street.

His involvement in the community led later on to other work in that area. He was Chair of the Tayside Community Relations Council that commissioned and released the report in April 1987 that detailed the scale of racism and racial abuse present in the city at that time. A month later he was appointed to Tayside Regional Council’s Equal Opportunities Committee as an adviser on Ethnic Minorities Organisations.

These two examples show how he was a part of not only the Bangladeshi community, but also the wider community in Dundee. As he grew older, this involvement changed in a significant way.

He gradually sold his restaurants, and moved into property management. At the same time, he focussed less on money and material things, to concentrate more on his Muslim faith. Both his son, Kader Chowdhury, and his friend Abu Karim mentioned that he changed during this time. He wore more traditional dress, he smiled more, the way that he moved changed, and the way that he spoke became more creative. For example, Abu Karim mentioned one incident when he had asked Kalam Chowdhury why he felt he had to wear Muslim clothes all the time when the Muslim religion is the religion for the world? He replied “If you see a dancer, how do you know they are a dancer unless they wear the clothes of a dancer?”

He became a highly respected elder of the community, someone that people approached to resolve difficulties and disputes – another area that Abu Karim thought was helped by the management skills Kalam Chowdhury had acquired in his jute training. As he became more religious he also spoke more about his faith, preaching at the Mosque and visiting families to provide pastoral support. When the new Mosque in Dundee opened, he spent much of his time there, praying and worshipping. He also welcomed visitors from the community and further afield, speaking about the Muslim faith. He was noted in the community for how well he spoke about this, with his son mentioning that his father had once even persuaded an atheist about the existence of God. Abu Karim stated that Kalam Chowdhury’s desire was to praise God in everything that he did, and to encourage everyone with their faith so that they were all included in heaven, because he didn’t want to go to there alone.

When he died in 2015, he was greatly missed in the community. He had played an early role in bringing the Bangladeshi community closer together through his desire to support people in times of crisis. He had tried to help highlight racism in the city in order to get rid of it. He had also tried to support people in their daily lives, and in living a better religious life through his work in the Mosque. Above all though, people missed his kindness, his character, and they missed his smile.

Written by Ruaraidh Wishart, Abertay University Archives

Sources

Interview with Kalam Chowdhury on Colourful Heritage site - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RzvVcw9-VM0

Archives held at Abertay University Archives - https://www.abertay.ac.uk/about/the-university/archive/ :

· Student Card of Abul Kalam Chowdhury

· Interviews conducted with Kalam Chowdhury’s son Kader Chowdhury (ref: AY25-EP-2-1), and Kalam Chowdhury’s friend Abu Karim (ref: AY25-EP-2-2) in 2020

Articles from the Dundee Courier and Advertiser Evening Telegraph in the British Newspaper Archive:

· Dundee Courier and Advertiser 4 April 1987 “Tayside has a racial prejudice problem, claims shock report”

· Dundee Courier and Advertiser 12 May 1987 “Equal Opportunities Advisers”

Comments